[Editor’s note: This is an oldie-but-goodie, originally published July 11, 2015. Re-releasing it, because it’s as timely as ever. By the way, how is Miller Huggins in the Hall of Fame, but Gene Mauch isn’t?]

July 23, 1961 was a notable day in Gene Mauch’s managerial career. At the age of 35, he was in his first full season leading the Philadelphia Phillies. His team lost 11-5 to the Chicago Cubs that day, the start of a 29-game stretch in which the Phillies won just once. This included a 23-game losing streak, the longest in baseball since the 1800s. His team occupied last place for 125 consecutive days and finished the season an astonishing 60 games below .500, and 46 games out of first place.

But Mauch was not easily discouraged. The following year he had a winning record, and by 1964 the Phillies were in the thick of a pennant race that would become legendary, involving personalities like Jim Bunning (future U.S. senator), Fred Hutchinson (who has a cancer treatment center named after him) and Curt Flood (who later went to the Supreme Court in the first test of free agency). Over a 28-year career as a manager, Mauch went on to win 1,902 games, the highest such total compiled by someone not in the baseball Hall of Fame.

It’s also the highest victory count for a manager who never reached the World Series. Mauch is perhaps best known for the agonizing ways his teams missed winning pennants. The 1964 Phillies famously blew a 6.5 game lead with ten days remaining in the season, losing ten straight games, the first seven of them at home. His 1986 California Angels were one strike from the American League championship when they surrendered a two-run home run to Boston, allowing the Red Sox to take the title.

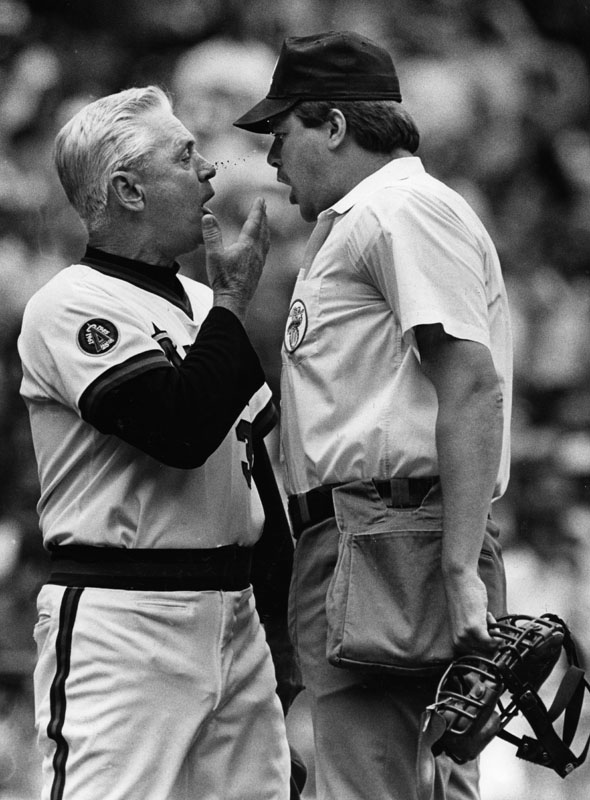

But that’s not all he’s known for. Mauch was a great innovator. He pioneered much of modern baseball’s game tactics, including “small ball,” where bunts and stolen bases are used to “manufacture" runs, defensive shifts, and the “two for one” substitution, which constructively arranges the batting order in late innings. These maneuvers worked, and are standard operating procedure today. While he was much-copied, Mauch wasn’t much-liked. He had a fiery personality, argued with umpires, snarled at reporters and, while always loyal, often became frustrated with his players.

I’ve always found it intriguing that baseball's field leaders are uniquely called managers rather than coaches. Coach implies a teaching/motivational sort of role, while manager suggests something multi-dimensional, a broker of information, knowledge and resources aiming to fulfill a strategy. Mauch took modest raw materials and achieved impressive results with his innovative methods. He raised his profession to a new level.

While Mauch was changing the game in the '60s and '70s, the field of organizational management was undergoing evolution. Just as he brought systematic approaches to his craft, the “science” of business administration was taking root, with data analysis and systems thinking becoming new norms. Looking back at this era, we can see the benefits and limitations of this approach.

Through the 1961 meltdown and the 1964 collapse, Mauch primarily used baseball tactics to try to correct events going very badly. On examination, his solutions appear mismatched to the actual problems. He was leading a group of people that had lost confidence in their ability to execute. The core troubles were in collective and individual morale. The situation may have called more for a supportive coach than a tactician, more psychology than lineup-jockeying. Mauch devoted slight effort to that front, and may have burned out some of his staff through overuse as the ship itself went down in flames.

Today, successful baseball and workplace managers are skillful at building highly functional work groups. (And not coincidentally, we almost always refer to these groups as teams.) They identify where staff need support, understand different personality types, are hip to different cultural contexts, and have “soft” skills that make systems work on both tactical and human levels. Managers in both environments must effectively manage egos, something Mauch had little patience for.

But that was another epoch, with different expectations—few people talked about the touchy-feely side of managing people at the time, and many of the archetypal leaders of the day (think Vince Lombardi) made Mauch look gentle by comparison. We can learn a lot from the way he systematically analyzed situations and identified orthodoxy-defying approaches.

A longtime chain smoker, Gene Mauch died of lung cancer in 2005. You won’t find his photo in Cooperstown, but you’ll see his legacy every time you watch a baseball game.

Image Source: Public Domain | Water and Power Baseball in Early LA